Turkish Miniatures

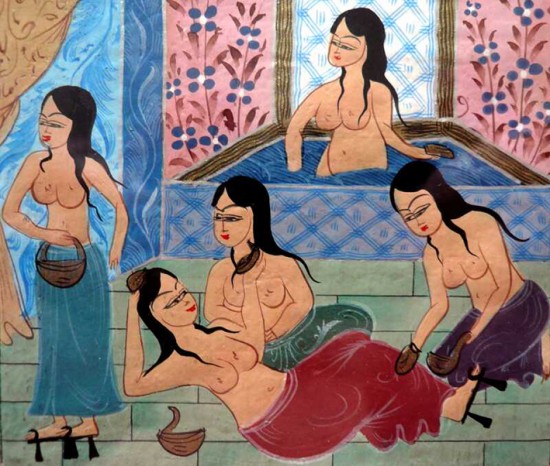

Five fishermen dressed in multicoloured robes and turbans gather their fishnets near the shore. It must be spring. Beside cypresses grow violets, daisies and lilies. Fishing has been abundant and soon seagulls will appear trying to catch their share of the booty. On a similar vegetation, next to a haima, the harem entertains a gentleman. Two women play the lute for his ears while other offers coffee to him. Another harem enjoys a warm scented bath in a hammam.

As these I was passing, one after another, pages once attached to a book and now dismembered. Endless pages, each so beautiful, decorated with fine flat colours and gold leaves. Gently profiled. Full of patiently hand-drawn calligraphy. Pages that slid in front of my eyes while changed in my hands in the dark background of a dim store in Divanyolu Caddesi, Sultanahmet district in Istanbul, more than once the centre of the world. First time when Constantine the Great made it the new Rome and left being the insignificant Byzantium, ancient Greek polis. Near the Seraglio palaces and temples where domes and minarets raise skyward is the Hagia Sofia Constantine ordered built when he changed the name of the city for his own and that Mehmet the Conqueror converted into a mosque after conquering the city in 1453. Or Camii Sultan Hamet, the famous blue mosque that would outnumber the minarets of the Holy Places oratories.

Figurative illustration or human representations are uncommon in Islamic culture, almost even in the Christian Constantinople after the iconoclast uprising. In the absence, Islamic art figurative vehicle was replaced by the word: writing. The Arabic alphabet took volume and ornamental calligraphy develops in pictorial aspects, sometimes with geometric, zoomorphic and floral motifs forming beautiful Bismillah or sentences that build endless profiles in designs almost impossible and hard to read.

However, east of the Muslim world, there was a developed tradition employing people and animals in pictorial representation. Its origins date back from the times of the renowned school of Samarkand, where their artwork workshops were made in wood, paper or leather. Their heirs were, between eleventh and thirteenth centuries, the Seljuk Turks in Anatolia. In the Middle Ages created wonderful works accompanied by rich illustrations, as Maqāmat by Al-Qāsim Ibn-Alī al-Ḥarīrī, bound in Baghdad in 1236. Also maps, between mapping and precious landscape, like Istanbul and Galata by Matrâki painter did in 1536.

Illustrated miniature masters core was forged in the Persian Empire where the Safavid dynasty, particularly bibliophile, continued the brilliant artistic tradition of the descendants of Tamerlane, in Herat. Initially, compositions were designed only to illustrate manuscripts. In Persia the development of a book was a complete and complex art, from paper crafting, to the contents, and also the carefully binding, as showed in some of the illustrations preserved in the Library of Tabriz.

Beyond the Sublime Porte Sultan Mehmet II employed miniaturists in his court, in the Topkapi Palace, where shadowy halls savoured in one's desire and others indifference he established a workshop and academia: Nakkashane-i Rum. They also painted portraits of Turkish sultans, images of epic battles and scenes of court life from the Istanbul Seraglio. To this would be added the Persian school: Nakkashane-i Irani. The first were specialized in documentaries that told the biographies of their leaders, with their portraits and historical events occurred during their reigns. These works are known as Shehinshahname, rulers’ public and private lives. Completed in 1579 Kiyafet al Insaniye fi Gemaail al Osmaniye is the title of a great book by Seyyid Lockman that glosses life of Turkish rulers. Master Osman Nakkas handled the dozen portraits that illustrate it. Persian school would rather concentrate on poetic works.

Along Suleiman the Magnificent and Selim II reigns, in the sixteenth century, were already recognized thirty teachers who led the Ottoman miniature to its golden age. Master Matrakçi Nasuh developed topographic gender representing cityscapes completely devoid of characters. He portrayed streets and walls that once defended the Golden Horn, also Boğaziçi Strait, the Bosporus that links Marmara Sea waters with Karadeniz, Black Sea.

In the seventeenth there were more than a thousand artists working for a hundred workshops. The works were usually made by a full team. Miniatures were worked as can be done today by any animation studios crew. A painter developed the main scene and design. Subsequently trainees traced contours and filling with flat paints the lacking perspective. Scenes finally were finish applying egg white, starch, lead carbonate, ammonia gum and salt.

The miniature became popular among the inhabitants of Istanbul who requesting commissioned their paintings to artists working in the Grand Bazaar, the covered maze of shops.

© J.L.Nicolas